Picking the right hardware is critical, but make sure to include the controller programming software in the evaluation process as it will determine ease of use.

When selecting a controller for factory automation, it’s not just about whether a PLC, PAC or PC should be used. It’s also about defining the requirements for the application, including control basics and scalability for the future.

This article looks at some of the requirements to consider when choosing a controller for factory automation to ensure the hardware and software are right for the application and are future proof. The programming software platform can be just as important as picking the right hardware, so it needs to play a big part in the evaluation.

For machine or process control, typical families of controllers include programmable logic controllers (PLCs), programmable automation controllers (PACs) and industrial PCs (IPCs). There are many differences among these controller types, but their features and functionality are merging.

While the PLC was first to the game as a relay replacer, and it remains the best choice for small- to medium size-applications, its capabilities are growing as new technologies are adapted. Many lower-end models use ladder logic programming, which is sufficient for most applications. More expensive PLCs allow the use of function block and other IEC 61131 languages.

The PAC adds capabilities to the PLC including improved motion, safety and vision capabilities. PLC-based PACs are also available as a subset of this class of controllers, providing PAC power with PLC ease of use. IPCs are a good choice for the most complex applications due to their more advanced features and the ability to work with additional languages such as variants of C.

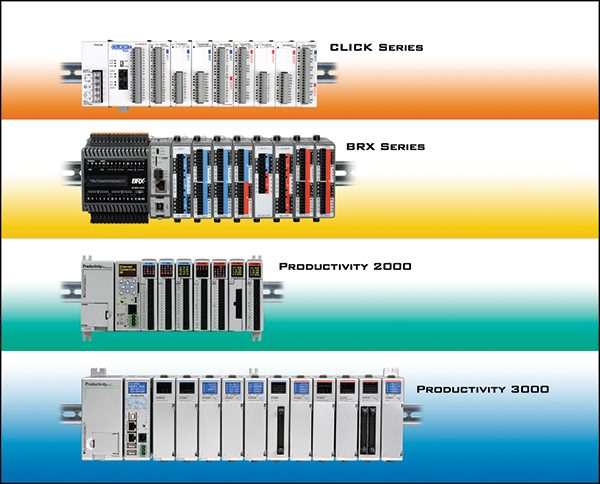

Regardless of which controller family is chosen, vendors offer a wide variety of controller form factors within each family, from small to medium to large. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Within each family of controllers, there are many configuration options, and different combinations of built-in and remote I/O. Communications options also abound, from simple serial to Ethernet. Hardware configurations may also include standalone controllers with built-in I/O, often called bricks, that often can be expanded with stackable I/O and rack-based options.

Controller Selection Considerations

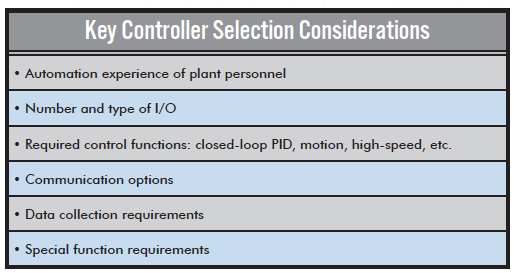

While understanding the specifications of the controllers being evaluated is critical—application requirements, plant personnel capabilities, and future connections are also important factors in the decision process. Some key controller selection considerations are listed in Table 1 and discussed below.

Table 1

Some facilities are very automation savvy and able to handle a wide range of controllers and equipment, while others have limited familiarity with newer technologies. PLCs are the primary automation tool for many industries and applications because they provide accurate, reliable and modifiable control, while being easy to work with due to their widespread use and familiarity.

If plant personnel are new to PLCs, then a small and simple controller is a good choice. These types of controllers are the easiest to use, but can be easily expanded, and have many of the features of larger PLCs.

Application Drives Selection

With plant personnel capabilities understood, the next step is examining application requirements. A good starting point is to estimate the number of discrete and analog input and outputs. A list of major components, such as actuators and cylinders—along with sensors, such as position and presence—will help determine an accurate count.

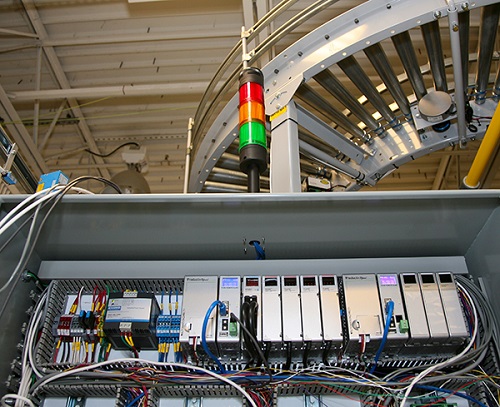

In addition to discrete machine and analog process functions, some PLCs have evolved to perform complex tasks such as motion and PID control (Figure 2). This type of controller can handle complex applications such as a high-speed packaging line using registration alignment or synchronized velocity control with encoder feedback.

Figure 2

Servo and variable speed drives used for some motion control functions usually don’t require coordination, but can still be quite complex in terms of communication and other requirements. There are many controllers available that can communicate to multiple drives at one time to command position, speed or torque. RS-232, RS-485, Ethernet and other options are all valid choices to communicate to drives. Digital communication protocols such as these are the better choice as compared to discrete I/O because they simplify wiring, allow more parameters to be monitored and commanded, and are more flexible to accommodate changes.

Data collection requirements should also be considered. Fortunately, many controllers, even some of the new small PLCs, have not only communications built in, but also data logging, web server access and email capabilities. The ability to write data to micro SD cards is another feature worth having in many cases, along with web server functionality and remote access.

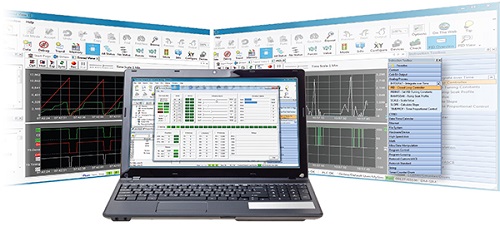

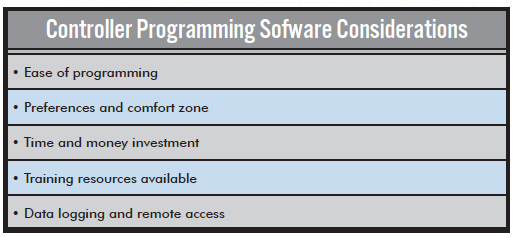

Some applications require safety ratings to meet regulatory requirements. While the application may suggest use of a safety-rated PLC, considering a non-safety rated PLC along with one or more programmable safety relays can greatly reduce cost, while still providing the required functionality. Software Determines Ease of Use Software programming is about half the effort on a typical automation project, but the time required to program the controller and the required level of expertise can vary widely depending on the controller programming software (Figure 3). Table 2 lists some of the leading considerations for evaluating software.

Figure 3

Simple, and sometimes free, software with limited programming instructions covers most applications suitable for use with these small controllers. While some controllers may only have 20 or so types of instructions—such as contacts, coils, timers and counters—this is usually sufficient for small applications. As machine size and complexity increases, most midsize and larger PLCs provide software platforms with many instructions, but these take longer to learn than their simpler counterparts.

Controller programming software choices often have much to do with a user’s preferences and comfort zone. While the hardware required is directly driven and determined by the application requirements, selection of software is often more of a subjective decision. Many programmers have a strong opinion of what software is better, but for most companies, it’s best to enforce a standard controller programming platform, along with consistent methods of programming.

Users should consider training resources available when selecting programming software. The Internet and growth of multimedia has changed the way programmers learn and develop applications. Huge libraries of technical information and user manuals exist online. However, not all suppliers are created equal when it comes to training resources, so careful evaluation is a must.

Some suppliers have extensive online documentation, and also have videos embedded directly in the software development platform. This quickly improves understanding and fluency with the programming software.

Table 2

The availability and cost of tech support should also be considered. Some suppliers offer free tech support, with phones answered quickly by technical experts. Others charge for this type of service, with their free service limited to automated and usually frustrating and useless canned responses.

Once the software program is developed, it needs to be tested. The programming software should include the ability to view PID loop response and motion profiles, and to simulate other functionality in software. Built-in project simulators can be a huge timesaver allowing code to be tested without the hardware present or before being downloaded to an existing system.

There are many considerations when selecting the right factory automation controller for your application, in terms of both hardware and programming software. For all but the smallest company, it’s unlikely one size controller will fit all, so it’s better to instead pick the right family of controllers, one capable of handling the entire range of your company’s requirements.

To read more articles from Automation Notebook, click here.

*Originally published: April 17, 2018