Opinions abound, but the facts show U.S. manufacturing to be a global powerhouse evolving to meet tomorrow’s changing needs.

Since the early American settlers began making their own goods in their new homeland, U.S. manufacturing has been an engine of incredible wealth. In simply meeting the essential needs of life – providing food, clothing, shelter, and safety – it has created a standard of living that benefits hundreds of millions of people, not just domestically but also abroad.

Where riches are plentiful, however, so too are thieves. From the shop floor to the boardroom, from Wall Street to Capitol Hill, in courtrooms and in union halls, innumerable profiteers have glommed on to American industry, putting enormous pressure on the system keeping us, and them, alive. The good news is that, despite the strain, U.S. manufacturing remains strong and its better days, believe it or not, are yet to come.

Alive and Well

Last year, the National Association of Manufacturers released a report on the state of U.S. manufacturing. In contrast to the bleak picture often portrayed on TV and in newspapers, The Facts About Modern Manufacturing reveals a dominant industry that’s one of the primary contributors to America’s success.

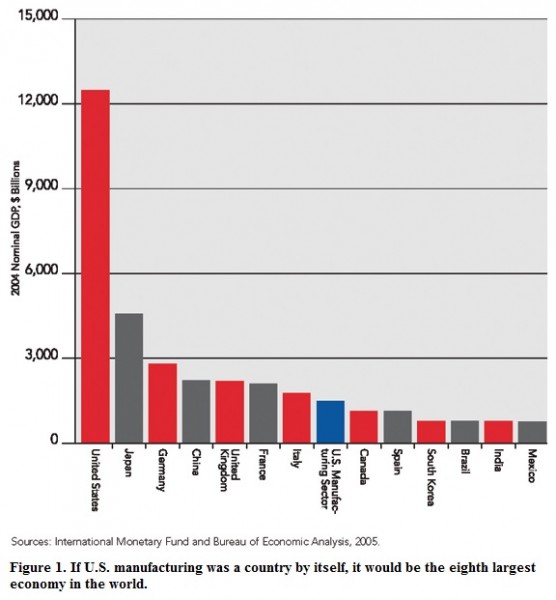

“Manufacturing output in America is at an all-time high, playing a central role in our economy,” says John Engler, president of the National Association of Manufacturers. “If it functioned on its own, U.S. manufacturing would be the eighth largest economy in the world,” he adds.

“All too often, the perception is that American manufacturing’s heyday is in the past, but nothing could be further from the truth,” says Jerry Jasinowski, president of the Manufacturing Institute, the research and education arm of the National Association of Manufacturers. “The facts show that manufacturing drives economic growth, productivity, and innovation in the U.S., and will continue to do so for years to come,” he adds.

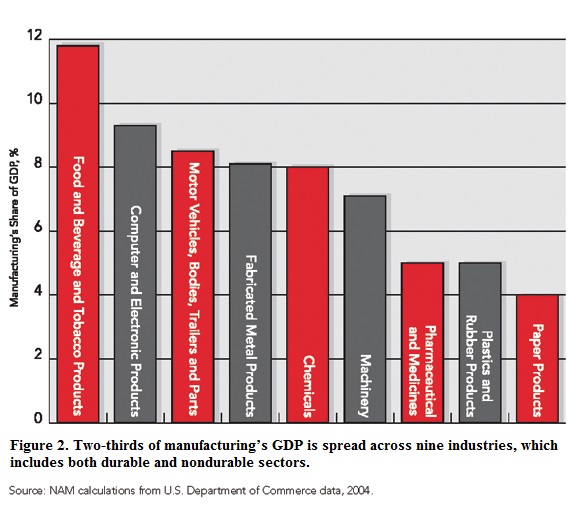

One of the key observations made in the report is that manufacturing influences the U.S. Gross Domestic Product more than any other market segment. Its contribution to real growth since 2001 ranks highest among all sectors at 15 percent. In 2005 alone, manufacturing contributed $1.5 trillion to the GDP and it continues to grow faster than the economy overall.

This upward trend, according to the report, owes largely to improvements in productivity. Over the past decade, manufacturing productivity more than doubled. Today, more goods are made in America than any time in U.S. history. The casual observer may equate productivity to widgets per minute, but in the big picture, it’s measured in wages and benefit compensation. In fact, productivity growth is “perhaps the single most important determinant of average living standards,” says Ben Bernanke, Federal Reserve Chairman.

Another relevant fact in the report is that manufactured goods account for more than 60 percent of the products America exports, helping offset the cost of what we buy from abroad. What agricultural exporters bring in each year, about $50 billion, manufacturers take in each month. This is especially weighty in light of the claim by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan that the three sources of original wealth are agriculture, manufacturing, and mining.

Besides its role in producing new wealth, manufacturing has a huge multiplier effect on the economy. Each manufacturing dollar generates an additional $1.37 in economic activity.

Manufacturing also provides nearly half of all corporate taxes collected by state and local governments, while funding more than 70 percent of the R&D conducted in the private sector.

Facing Challenge

In its recent report, the National Association of Manufacturers makes it clear that, although U.S. manufacturing is strong, it is continually being challenged on many fronts. “Manufacturers in the United States face unprecedented challenges ranging from rising energy and health care costs to a shortage of skilled production workers, scientists, and engineers,” warns John Engler, NAM president.

One area where America’s dominance is in jeopardy is our investment in research and development. The U.S. presently accounts for 40 percent of all R&D spending in the industrial world, but the ratios are changing quickly, and not in our favor, because federal spending has fallen in the past 20 years. In 1985, America invested 0.25 percent of the GDP into R&D; today it’s only 0.13 percent.

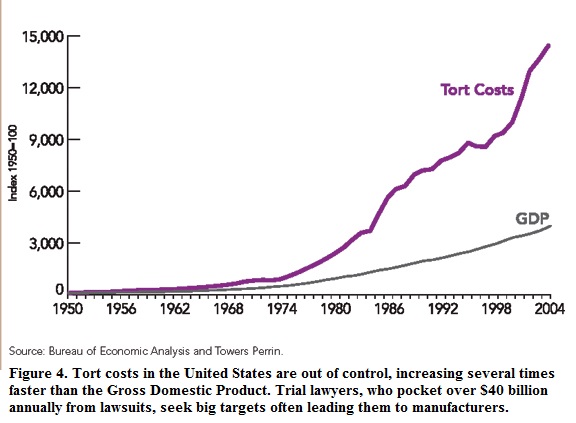

“Since World War II, federal support for industrial research has been a key source of American innovation,” Jasinowski explains. “But R&D spending is now half of its mid 1960’s peak, when it was two percent of the GDP.” By comparison, the United States now spends two percent of the GDP on tort claims, making the loss of R&D support even worse.

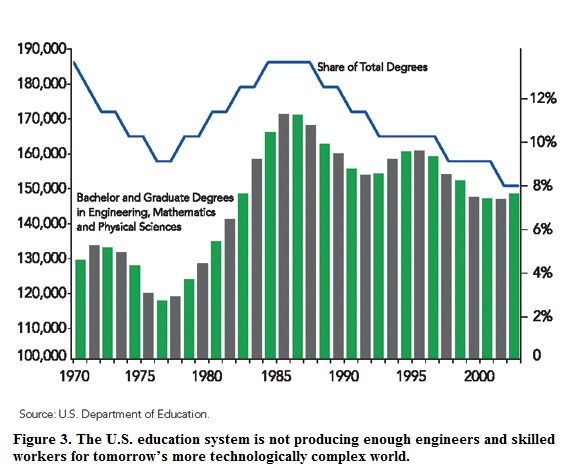

Another challenge facing manufacturers is a growing manpower shortage. In a recent survey conducted by the Manufacturing Institute, over 80 percent of manufacturers said they could not find qualified workers to fill open positions. Compounding the problem, our colleges are producing fewer engineers and our high schools are graduating fewer seniors with the skills necessary for today’s more technical jobs.

According to the report, in 2000, 23 percent of all undergraduate degrees awarded globally were in natural science or engineering. The U.S. was far below the average at 11 percent, while China, at 50 percent, was far above.

Perhaps one reason fewer people are going into engineering is that our runaway tort system makes it much easier to take wealth than create it. Rising tort costs are, in fact, one of manufacturing’s biggest concerns. Although the U.S. economy is growing at a healthy clip, tort costs are increasing many times faster, a trend that seems to have started around 1974. In Japan, France, Canada, and the United Kingdom, tort costs are less than one percent of the GDP; in the U.S., they’re more than double, amounting to $250 billion a year, much of it sucked from the manufacturing sector.

Another challenge cited by the report involves government regulations. In 2005, the regulatory load on U.S. manufacturers was $162 billion, 32 percent higher than that imposed on manufacturers by our nine biggest trading partners. Manufacturers also face higher taxes in the U.S. The corporate tax rate here is about 40 percent, compared to 28 percent, and falling, in developed nations with which we compete.

Rising health care costs are yet another concern. Driven by escalating malpractice claims and insurance premiums, health care now consumes up to a third of the revenues manufacturers bring in. Were it not for these structural (non-wage) cost disadvantages – health care, taxes, liability, and regulatory expenses – manufacturing in the U.S. would be more economical than in Germany, France, Canada, and the U.K., and roughly on par with South Korea.

Perhaps the most complex challenge facing American manufacturers is that of exchange rates. The stronger the dollar relative to a trading partner’s currency, the more difficult it is to command a fair price for goods. Exchange rates, the report claims, triggered the manufacturing recession of 2001. Unfavorable rates caused exports to drop from $771 billion in 2000 to $681 billion in 2002. When exchange rates were realigned in 2004, U.S. exports soared to over $900 billion the following year.

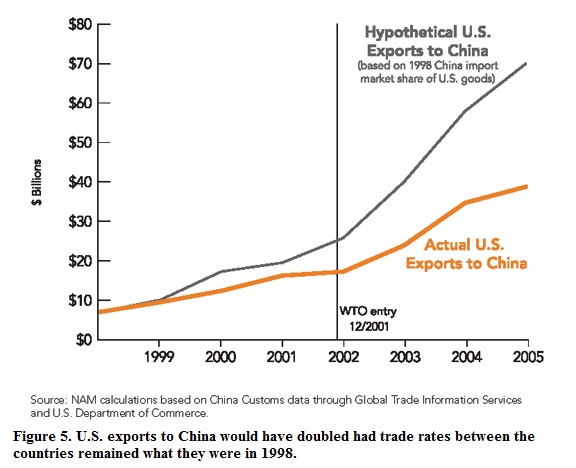

Establishing fair rates with China is especially difficult. China artificially pegs its currency to the value of the U.S. dollar. Worse, since 1998, it has continually reduced the percentage of U.S. goods it imports. Because of this growing imbalance, the U.S. is no longer the largest exporter in the world. That distinction now belongs to Germany, not surprising given that China imports 50 percent more goods from the European Union than the U.S.

Another disadvantage U.S. manufacturers have when trading with China is their inability to enforce intellectual property laws. Losses associated with stolen IP add up quickly and are rarely recovered.

Getting Stronger

From its golden past to the rock-solid foundation it operates on today, U.S. manufacturing is on a course that not only will rise to meet the latest challenges, but also scale new heights as manufacturers evolve to meet the needs of our rapidly changing world – here as well as abroad.

An example of the sorts of changes we’re likely to see can be found along the path of the U.S. bicycle industry. During the height of its success, Schwinn was one the top bike makers in America. In its main Chicago plant, it manufactured rims and frames, onto which it assembled gears, brakes, pedals, hubs, and other parts that it imported from as many as eight countries. In addition to being a smart manufacturer, Schwinn was an intelligent marketer, able to anticipate if not influence consumer trends and then develop products that met the demand.

Schwinn eventually succumbed to the strain of the many challenges manufacturers face, but in its place, several new U.S. bicycle makers emerged following a fairly similar formula. Targeting high-margin niches, companies such as Cannondale, Haro, Specialized, and Trek have come of age, employing high-value manufacturing processes that turn out customized frames in a variety of styles and sizes.

What happened in the bicycle industry – reminiscent of a cell dividing into multiple units – is about to be repeated in many industries in many ways, catalyzed by advances in automation technology. Even in the auto industry we may see new U.S. manufacturers, and perhaps old ones reborn, all moving more quickly and effectively with the help of programmable automation.

In a nutshell, programmable automation is the means by which manufacturers are achieving software retoolable factories. It is likely to bring about a renaissance in manufacturing in large part because it is scalable. With reduced entry costs, teams of talented people will more easily form to serve high-value, high-margin manufacturing niches, whether it’s cars, clothing, health and wellness, household appliances, or food.

Besides encouraging startups, programmable automation also upgrades the roles of everyone in industry. Not long ago, equipment operators spent the majority of their time turning cranks

and dials and loading machines. Today, factory workers run machines primarily through computers, spending much of their time fiddling with the virtual equivalents of yesterday’s cranks and knobs.

Tomorrow, however, is a whole new ballgame. Operators working in intelligent automation environments will no longer be buttonpushers because machines will run themselves. People, meanwhile, will function at a higher level, interacting with the process rather than the equipment. This will allow operators to spend more time improving quality, throughput, and yield.

Of the many indicators pointing to the coming revolution in industrial automation, the most convincing is upward programmability. The age of intelligent programmable components is here, and it is giving rise to a new era of intelligent machines and processes on which programmable automation is based. Programmable automation is hierarchical and now made possible by intelligent machine components that can gather, process, store, and share information across industrial computer networks.

The U.S. is especially well positioned to excel in this area because a large portion of industrial R&D is dedicated to computer hardware and software. Nearly 30 percent of America’s industrial R&D budget goes to computer technology, compared to the 15 percent allocated by other countries. This broader distribution of industrial R&D in the U.S. will also pay dividends by expanding our knowledge in the many domains where automation is applied.

All this is likely to stimulate even more investments in manufacturing in the U.S., accelerating growth that much more.

“Some mistakenly believe manufacturing in the U.S. is in decline,” says Dennis Cuneo, senior vice president of Toyota Motor North America, one of the sponsors of the National Association of Manufacturers report. “On the contrary, U.S. manufacturing is vibrant and robust,” Cuneo says. “In fact, we believe the United States will remain the biggest and most successful competitor in global manufacturing, and we intend to help it do so by continuing to expand our investment in American manufacturing.” And Toyota, to be sure, will not be alone.

To get a copy of The Facts About Modern Manufacturing published by the National Association of Manufacturers, log on to www.nam.org/facts.

By Larry Berardinis,

Editor, Motion Systems Design

Larry Berardinis Bio

Larry Berardinis is Chief Editor of Motion System Design, prior to which he was Managing Editor for Machine Design, covering electronics and motion technology. He also worked as an engineer at Cincinnati Electronics Corp., developing optical sensors and automated measurement systems, and as an intern at NASA Glenn Research. A member of Eta Kappa Nu, he has a Masters of Science in Solid State Electronics from the University of Cincinnati and a BSEE with a physics minor from Cleveland State University.

Originally Published: June 1, 2007