Many industrial automation end users are not staffed to deploy cutting-edge cybersecurity provisions, but they all will benefit from performing attainable and practical basic steps.

By Tim Wheeler, AutomationDirect

Albert Einstein said, “Genius is making complex ideas simple, not making simple ideas complex.” Modern cybersecurity is an example of an extremely complex subject, where a lot of people are seeking some genius-inspired simple steps to start them on the right path toward being cybersecure. Most people—whether they explicitly realize it or not—already rely on carefully conceived personal/commercial cybersecurity provisions in their everyday life for activities such as web browsing, mobile access, and banking. However, how can anyone really understand all the details?

For industrial automation users, the cybersecurity struggle is compounded by the variety and vintages of devices and technologies present in their operations, and often in service for many years before cybersecurity was a serious consideration. The volume of cyberattacks continue to increase and the threats become more sophisticated, and both offensive and defensive technologies evolve. Furthermore, standards and regulations continue to be updated.

In the face of this relatively grim news, it is encouraging to remember that there are many back-to-basics steps that any industrial organization can perform to clarify and enhance their cybersecurity posture, and to set the foundation for future improvements. Also, industrial users should familiarize themselves with a few topics commonly discussed by industry, regulators, and standards organizations regarding cybersecurity.

Standards and Regulations

There are several cybersecurity standards, but two of the most relevant for industrial operational technology (OT) users are ISA/IEC 62443 “Security for industrial automation and control systems,” and ISO/IEC 27001 “Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Information security management systems — Requirements.” The United States Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) develops services, tools, and programs aimed at improving the cyber resilience of technology. More recently, at the end of 2024, the European Union Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) regulation has come into force and will impact industrial automation and control products and systems going to or from Europe, but it is too early to say exactly how.

New threats and even projected threats are constantly identified. As just one example, have you heard of “Q-Day,” which is term describing—perhaps mere years away—when quantum computing will make some current security standards obsolete? New information technology (IT) strategies are rolling out to address this, and they will need to be expanded past consumer and commercial uses and into the industrial domain.

Many end users and designers may not be staffed to understand the intricacies of cybersecurity standards, and the full impact of merging OT and IT systems, but they can look for suppliers and products certified as compliant with these standards (Figure 1). Regarding the EU CRA, this is a new regulation with a lot of potential to improve products with digital elements (PDEs), and it will introduce obligations and the potential for noncompliance fines.

However, there are some concerns with regards to general definitions in the regulation, such as “secure by design,” and on the impact of EU CRA on PDE used throughout industrial installations, especially around automatic update requirements, which is generally considered undesirable for validated production OT systems.

Cybersecurity Basics for Today

Eventually, there will be no way industrial automation implementers can avoid the need for pursuing a deeper understanding of cybersecurity details. Despite this outlook, there is some good news, because all cybersecurity provisions are built upon some basic foundations which can be instantiated today.

Performing an audit

Management consultant Peter Drucker is often quoted as saying “you can’t manage what you can’t measure.” Adapting this thought for cybersecurity leads to the idea that you can’t cybersecure what you can’t identify. Accordingly, the first step for any industrial cybersecurity effort is to perform a comprehensive audit of automation assets.

This includes obtaining the make, model, serial/license number, and firmware or software version status for any network capable device or application. Identifying the product source and country of origin is also becoming important. Performing a comprehensive audit task requires lots of legwork and investigation to dig through control cabinets and explore network connections.

Target tangible devices can include intelligent field instruments, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), human-machine interfaces (HMIs), edge controllers or PCs running Linux- or Windows-based applications, and more. Network connectivity for less significant assets is more intangible and can require additional software tools to discover unexpected wired and wireless connectivity onsite, and even spanning to remote locations or the cloud.

Physical Security

Physical security is probably the easiest understood cybersecurity topic. Once all new and existing industrial automation assets are identified by an audit, they should simply be physically locked up to the greatest extent possible, using a controlled method with access defined and logged for personnel with the appropriate privilege (Figure 2).

Control panels, electrical cabinets, and entire electrical rooms are some of the most likely locations for physical lockdown. Control rooms or any form of active HMI should be in a secured space. End users should ensure that all Ethernet switches or other potential entry points to the industrial automation network are locked up, which leads into the next item.

Network Management

Cyberattacks can be perpetrated via in-person access to USB ports and other network connections, but some of the most insidious assaults happen remotely from internet or wireless network connections. Decades ago, most OT automation existed as individual air-gapped systems with no convenient external connectivity. Today, with the wide adoption of IT technologies adapted for industrial use, almost any automation elements may be networked.

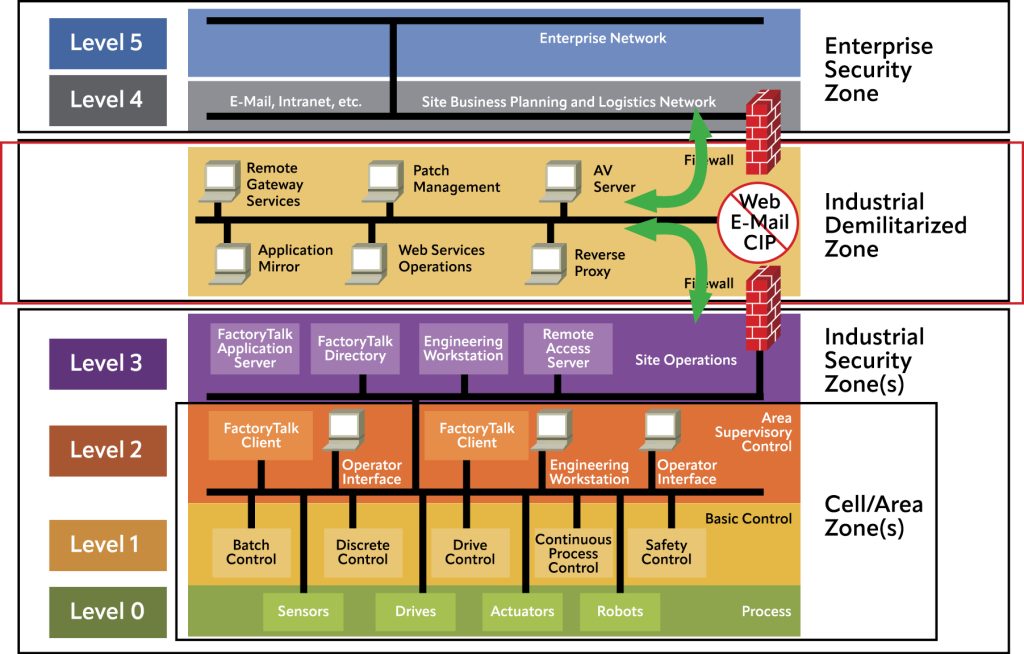

End users supporting existing automation or designing new systems can follow some ever-useful guidelines. For example, for OT systems it remains useful to preserve a degree of network hierarchy and segmentation, much like the classic Purdue Model (Figure 3). Although modern systems can be architected into much flatter and converged arrangements, a more segmented design restricts unexpected access by enabling just associated devices to interact. For example, field devices connect with their associated PLC, the PLCs connect with related HMIs, and PLC/HMIs connect with higher-level enterprise computing assets.

Of course, modern internet of things (IoT) protocols, internet cloud connectivity, and mobile devices make it possible for a smart field instrument to connect up through a PLC or directly to the cloud, and to then interact with a user’s mobile device. This type of connectivity can be beneficial, but it must be properly secured and managed. OT Implementers should enforce strict user management and authentication controls, usually enacted by and in conjunction with IT personnel, and based on solutions certified according to ISO 27001.

Researching Vulnerabilities

There is another important cybersecurity basic, typically much more confusing to users than the preceding steps, and that is to actively research vulnerabilities. This requires searching through information published by hardware and software vendors relating to known issues with their products. Responsible reporting of these security advisories is a sign of a quality vendor (Figure 4).

Figure 4: As part of a thorough commitment to providing cybersecure products, AutomationDirect maintains a website identifying known security advisories to help end users evaluate their installed systems.

An extremely useful tool for users is the CISA known exploited vulnerabilities catalog, available at the www.cisa.gov website. Researching vulnerabilities is an essential activity which must be initiated procedurally for risk mitigation. However, it can be a challenge for smaller and leaner organizations to perform, especially those operating under an “if it isn’t broke don’t fix it” approach.

Establishing Cybersecure Foundations

The consequences of cybersecurity failures in an OT context are many: downtime, waste, equipment damage, environmental incidents, and even compromised personnel safety. Industry does not have all the answers, and many end users are not staffed to implement esoteric new technologies.

However, foundational activities—such as auditing assets, establishing physical security, performing responsible network management, and researching vulnerabilities—are within the reach of almost any organization. Together, these activities will provide a basic level of defense and a foundation for additional cybersecurity provisions to be applied when possible.

All figures courtesy of AutomationDirect

About the Author

Tim Wheeler is the Cybersecurity Manager for Industrial Products at AutomationDirect. Tim is a veteran, with over 25 years of experience in the military and industrial sectors, specializing in automation, communication, and process optimization. He is skilled in developing and implementing streamlined solutions for complex systems.