Mechanical engineering students also took on the controls aspects for designing a flexible hydraulic press producing sustainable and cost-effective building insulation production.

By Ben Zamachaj

Worldwide, millions of people live without adequate housing. While modern building materials like fiberglass insulation, moisture wrapping, and even the humble cinderblock have markedly improved construction standards over the past century, there remain many places without access to these—figurative and even literal—building blocks. New methodologies and locally accessible materials can help create housing that is both adequate and accessible.

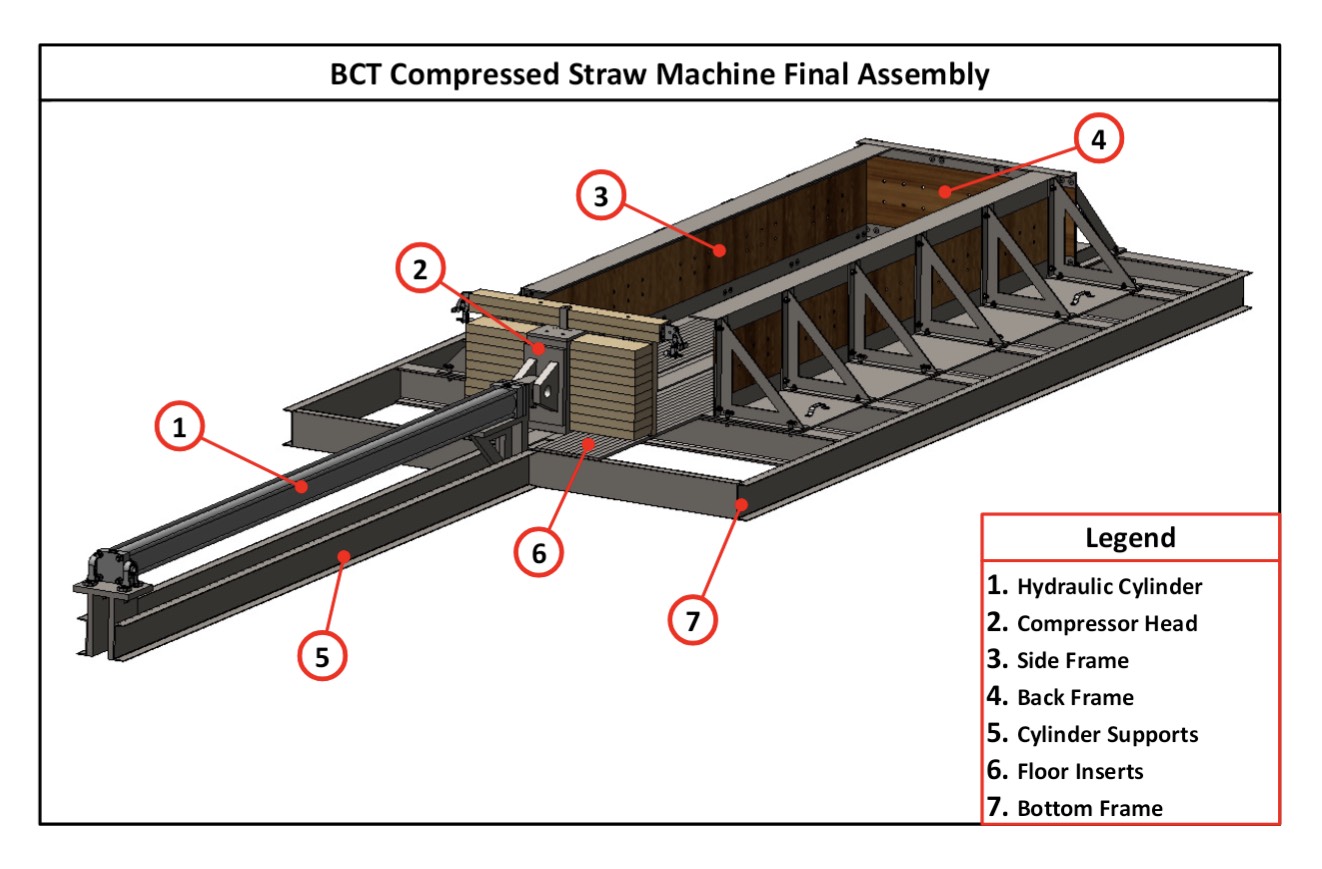

Ideally, any new manufacturing process would also be sustainable and environmentally friendly. To meet this seemingly impossible challenge, two teams of mechanical engineering students from the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass) Mechanical and Industrial Engineering department were assembled, sponsored by a local architectural firm. Their goal: create a machine that turns waste straw from wheat harvests into efficient insulated building panels—locally available, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The UMass straw panel presser uses a hydraulic cylinder and frame setup to produce the correct compression for straw insulation panels.

Our team focused on the project’s controls, while a second team worked in parallel on the device’s mechanical structure. This two-team project structure mirrors the interdisciplinary nature of most equipment and automation projects, giving students important real-world experience.

Compressed straw thermal insulation: the theory

Fiberglass—today’s de facto building insulation standard—works very well for keeping excess cold and heat at bay. However, producing it requires specialized processes that are not accessible everywhere, and that may not be environmentally friendly. At the same time, humans have been using straw as insulation—for example, in the form of thatched roofs—for millennia. Today, wheat harvests yield leftover straw, which is burned off as waste, or used as mulch. Using it instead as insulation not only provides an inexpensive source of this critical building component, but keeps carbon sequestered rather than releasing it into the atmosphere.

If this sounds too good to be true, there are two main challenges with using straw as a building material. First, straw is quite flammable in its natural form. Second, while straw may fall nicely in line as a traditional roof material, more modern construction methods demand it to be presented as uniform insulation panels.

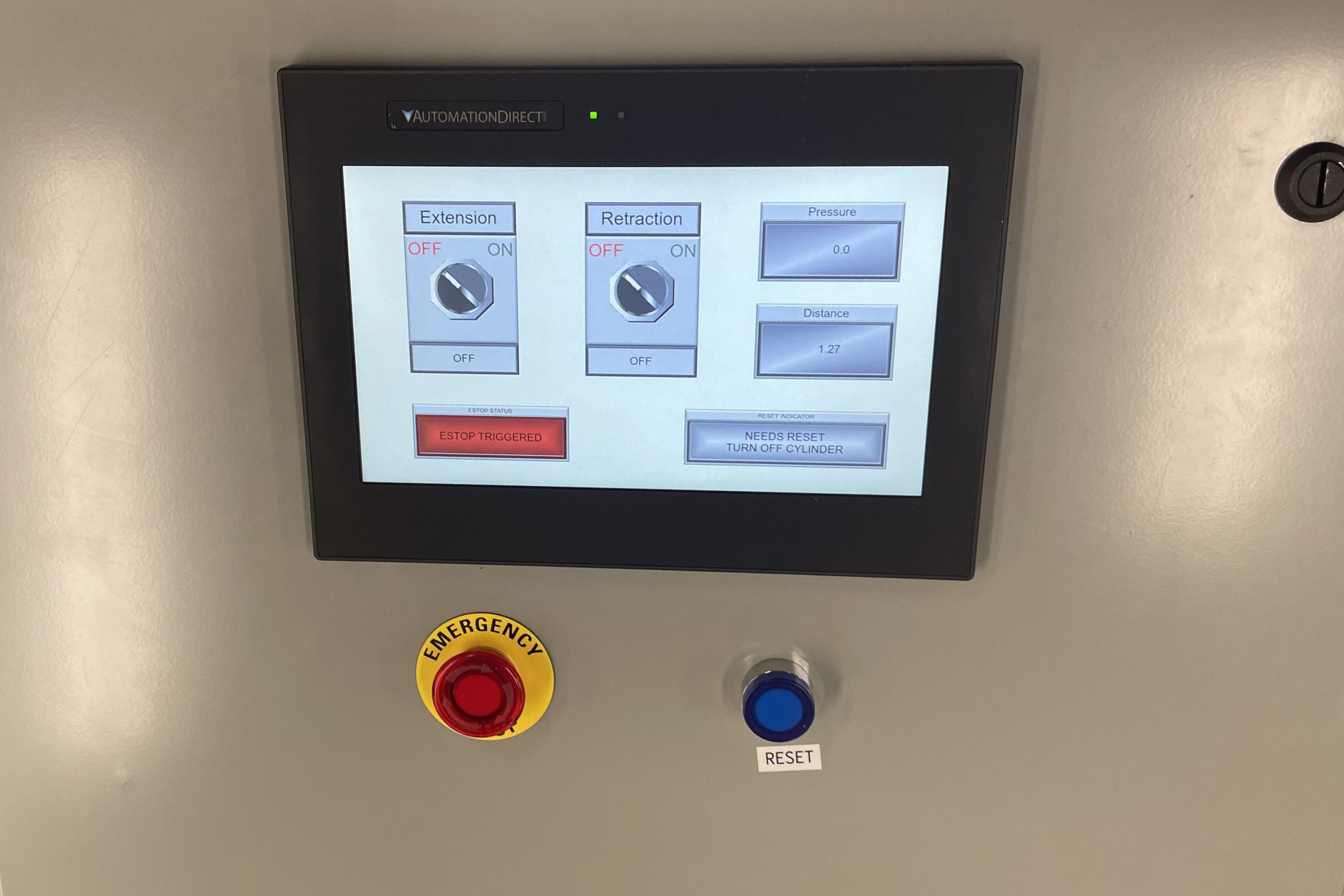

To meet these challenges, the two engineering teams implemented a hydraulic press with a wooden frame to hold the straw in place, an AutomationDirect C-more CM5 series touch screen human-machine interface (HMI), and a CLICK stackable micro brick programmable logic controller (PLC), along with other AutomationDirect-source components, to automate the panel presser system (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The design team chose an AutomationDirect C-more CM5 series touch screen human-machine interface (HMI), the CLICK stackable micro brick programmable logic controller (PLC), and other components available on the AutomationDirect website.

Processing also includes a subsequent step of applying a vapor barrier wrap. It was especially important and challenging for the controls-focused team to produce the proper pressure needed to achieve the target optimal straw compression. Under-compression of straw degrades the fire resistance, while over-compression is detrimental to heat insulation properties. To properly compress the straw without crushing it, multiple press cycles are used to construct each panel.

Pressing automation into practice

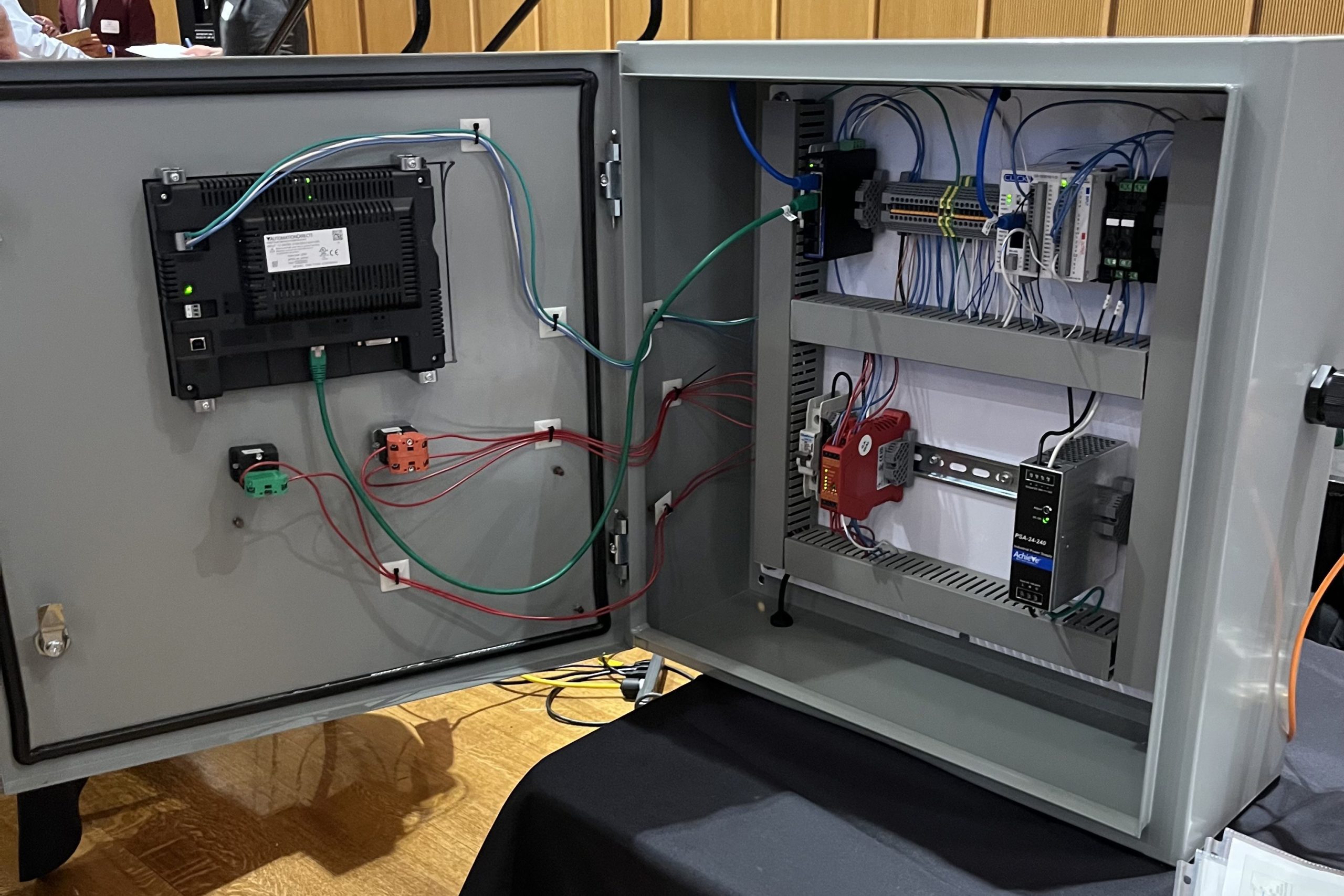

While the frame analysis, design and assembly were underway by the mechanical team, our team implemented controls, sensors, and supporting electronics sourced from AutomationDirect. After reviewing the website and evaluating the project requirements, we selected components including:

- CLICK PLC, C0-12DD1E-1-D Ethernet analog 24VDC

- C-more CM5 touch screen HMI, 10-inch

- Stride industrial unmanaged Ethernet switch

- Wenglor OPT2011 laser distance sensor

- Various control enclosure, terminal blocks, safety relays, proximity switches, and wire management products

- Pull-cable-type emergency stop switch and accessories

Care was taken to include extra space allowing for future expansion and modification as required (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A generously sized control panel was implemented, allowing for adequate wiring space and future potential upgrades.

Originally, the project was envisioned to have a more mechanical/manual focus, but when our team members completed Professor Jim Lagrant’s course on Industrial Automation we decided to switch to a PLC- and HMI-based system, we found that the free CLICK ladder programming and C-more HMI configuration software and concepts were intuitive and easy to learn. AutomationDirect offers many support options on the website, including manuals, data sheets, and videos. They also offer responsive phone support, and even provided a bit of welcome pushback at times if we had not fully performed our homework before calling. AutomationDirect’s online leadership in offering a range of support options helps users of all types engage in the ways that are most helpful for them.

The entire team contributed to specifying sensors and wiring the panel wiring, while my focus included writing the control program. Using interposing relays, the PLC controls a third-party hydraulic power pack and associated cylinder solenoids. The PLC also monitors the hydraulic pressure and the equipment position.

The 10-inch touchscreen allows users to set up the extension and retraction, visualize pressure and distance readings, and receive message indications. A physical cable pull switch around the machine and an emergency stop (e-stop) button provides a way for users to initiate an e-stop wherever they are. A 240VAC disconnect switch for the hydraulic power pack is also implemented to ensure that this subsystem is disengaged when needed. Together, these components allow for expedient control of the machine while keeping operators and equipment safe.

Quality equipment and controls yields reliable results

The UMass straw panel machine uses its 120-inch stroke, 4-inch bore hydraulic cylinder, along with sensor data to compress panels to a uniform density at the target value. Machine settings are adjustable via the system’s HMI, which shows process results in real-time.

While other systems have been designed to produce straw panel insulation, the UMass approach is much more affordable than alternate solutions. Furthermore, this machine enables the project’s sponsor to research the performance of compressed panels made from waste straw—and potentially other recycled materials—with a flexible finished panel size and compression process. Having all these options together, while being more affordable than competitors, enables further development without significant budget constraints.

The overall sponsor of this project was an architectural firm, and with this new process for making compressed straw insulation, they plan on building a home with it in Holyoke, Massachusetts. From there, one could see this insulation technology used to help create affordable, quality housing, with sustainable materials, in the United States and beyond.

Our team appreciates the support of Automation Direct with the PLC, HMI, and other control elements. With a wide array of product offerings, along with excellent phone and online support, AutomationDirect is a proven partner for those getting started with automation, and well as those who have been at it for decades.

Since completing this project, I have graduated with a mechanical engineering degree and now work as an automation engineer. Working with AutomationDirect products has springboarded my post-graduation career. Similarly, team members Samira Lopez, Graham Buckton, Peter Chen, and Om Naik, gained valuable insights into the world of PLC automation, hydraulic power… and even how straw behaves in compression. This project will serve as valuable experience as they move on to the next phase in their careers!

All figures courtesy of Ben Zamachaj

About the authors

University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass) mechanical engineering students (pictured left to right: Samira Lopez, Graham Buckton, Peter Chen, Om Naik, and Ben Zamachaj) formed one of the two teams executing this straw insulation and recycling project. Ben Zamachaj was controls team lead, and after graduating with his mechanical engineering degree he now works as an automation engineer at TTM Technologies in Stafford, Connecticut. Jim Lagrant, Professor of Practice in Manufacturing and director of the Masters of Manufacturing Engineering Program at UMass acted as the advisor for this project. (Credit: Jon Crispin)