The annual SourceAmerica® Design Challenge is a national engineering competition to design workplace technology for people with disabilities. For this competition, high school students spend months partnering with a nonprofit that employs people with disabilities to invent a device, process, system or software for a more productive work environment.

Kirby Harder, Copley High School’s (CHS) Industrial technology teacher, carefully hand-picked seven students to serve as the CHS Engineering Team. Along with Coach Fiona Casida, Harder partnered the team with Weaver Industries, a non-profit organization in Akron, Ohio, to develop a more efficient way to improve productivity at their production facility.

Weaver Industries maximizes the independence and personal fulfillment of individuals with developmental disabilities via vocational training and employment opportunities through community, business, and family partnerships. Their production services division, ProPak, boasts a 40-year history of providing businesses throughout the northeastern Ohio region, and the country, with quality service.

Fomo Products, a manufacturer of low pressure polyurethane foam insulation, sealants, adhesives, and spray foam systems in pressurized packaging, enlists the services of ProPak’s employees to produce Fomo Nozzles for their products.

For ProPak’s employees, the nozzle assembly procedure was awkward, fatiguing and done entirely by hand. Of their 30 employees, only five could perform the task. The seven-student CHS Engineering Team accepted the task of improving production by automating the assembly process. The team’s goal was to design and construct an assembly machine that would enable all ProPak employees to complete the assembly process as well as decrease the production time and cost per assembly.

In order to automate production, the CHS Engineering students visited ProPak’s production facility to gather data which would aid them in the design, fabrication and testing of a prototype assembly machine which presses a mixer into a nozzle to a specified depth required by Fomo Products.

In order to automate production, the CHS Engineering students visited ProPak’s production facility to gather data which would aid them in the design, fabrication and testing of a prototype assembly machine which presses a mixer into a nozzle to a specified depth required by Fomo Products.

The team quickly observed that the awkward assembly process required a large amount of fine motor skills and upper body strength.

The slow and awkward four-step assembly process was as follows:

- Sixteen empty Fomo nozzles were placed into a wooden assembly jig.

- A plastic mixer was then inserted into each nozzle.

- Using a hand tool, the mixer was pressed to a specific depth inside the nozzle.

- Completed assemblies were checked, removed from the assembly jig, and placed into a bin to be transferred to the packaging station.

The team also collected baseline production numbers, including parts per hour and minute, as well as any other applicable data ProPak had on file. Data was also collected by observing employees on the assembly floor. The fastest nozzle assembler produced one block of 16 nozzles every 64 seconds and four blocks every five minutes. Another employee was timed assembling one block in two minutes and 30 seconds, more than twice the time it took the fastest employee; this provided a better representation of the average employee.

After extensive data collection, the team returned to Copley High School to brainstorm on how to improve the assembly process. The team designed a machine that incorporated a 1-to-1 process, meaning that every preassembly placed into the machine resulted in a final assembly exiting the machine, instead of the current multi-step process. This new assembly machine incorporated the use of computer electronics and pneumatics to complete an effortless assembly process.

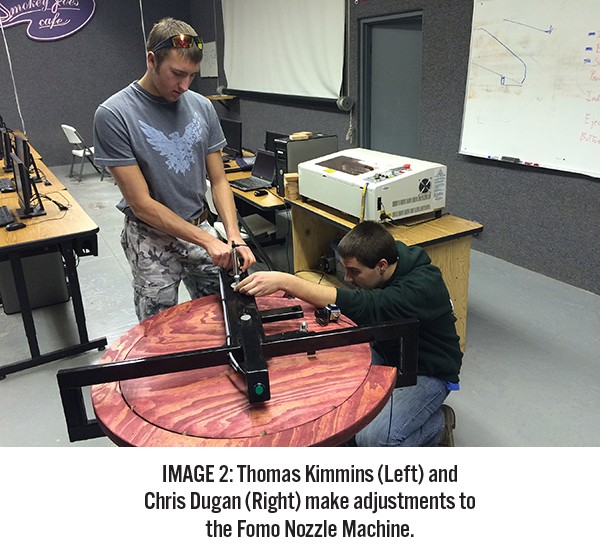

Using SolidWorks, the team generated a design and made machine sketches, then began building and testing individual parts. The newly designed Fomo Nozzle assembly machine was constructed of a slotted plywood center wheel and outside path with a cold rolled steel wheel center and axle, and steel tubing wheel frame. The indexer and plunger mechanism consisted of pneumatic cylinders and custom metal parts. Three removable plywood parts hoppers were constructed to contain the nozzle, mixer and completed assembly. Casters were also added to make the machine easily portable. The entire process is controlled by Arduino computer code written by senior Bobby Wagner.

Using SolidWorks, the team generated a design and made machine sketches, then began building and testing individual parts. The newly designed Fomo Nozzle assembly machine was constructed of a slotted plywood center wheel and outside path with a cold rolled steel wheel center and axle, and steel tubing wheel frame. The indexer and plunger mechanism consisted of pneumatic cylinders and custom metal parts. Three removable plywood parts hoppers were constructed to contain the nozzle, mixer and completed assembly. Casters were also added to make the machine easily portable. The entire process is controlled by Arduino computer code written by senior Bobby Wagner.

Wagner says, “The biggest thing I learned from this project was that by working together we can accomplish greater things than we ever could alone. For this project, if any of us had attempted it alone, none of us could have achieved a final product of comparable quality as the one we produced.”

Of course, not everything comes together as originally planned, or as it may appear on paper. There are always unexpected snafus, and when problems arise, the team has to work together to find the solution.

The team’s videographer, junior Aaron Hesketh commented, “Troubleshooting is often the most important part of a project. Just because you think something is the problem, if it isn’t, redoing it six times will not fix it. We encountered a few bugs while developing our machine, and we thought one of them might have been a loose connection in our wiring. So we rewired the whole machine several times, but in the end we just needed a new computer.”

Whereas the previous assembly process required employees to stand during the entire process, the team’s final design is at a height that either a wheelchair or standard chair can fit, allowing the employee to sit comfortably. The students improved the ergonomics by locating the plywood parts hoppers in convenient easily reachable locations on either side of the operator.

With the new Fomo Nozzle machine design, the operator can easily reach the raw material hoppers, drop the Fomo Nozzle into a slot on the center wheel, followed by a plastic mixer. Then the operator presses a single pushbutton which indexes the machine, presses the mixer to a specified depth and ejects the completed nozzle into the completed parts hopper.

Before the redesign, only five employees had the stamina to produce the Fomo Nozzles. This new process enables all 30 employees to assemble nozzles, a 500% increase in employee involvement. Production numbers have doubled from an average of 450 per hour to 900 per hour.

By automating the assembly process, production time was reduced from an average of eight to 12 seconds each to as little as 3.11 seconds per completed nozzle. With the CHS Engineering team’s design, there was also a decrease in part handling, assembly steps, and rejected parts were virtually eliminated.

Teachers know that if you can help your students learn more than just the steps given in a lesson plan, those students will become not only more intelligent but also wiser in the process. This team of students quickly learned that designing and constructing this machine for Weaver Industries was more than an engineering lesson.

Reflecting on the overall project, student video spokesperson senior Chav Maharaj says, “I believe that the biggest thing we learned from this whole experience is to not take things for granted. Throughout the whole project we would often have to rethink concepts to try to make our machine versatile to all the current and future employees at Weaver. In order to complete that, we would have to put ourselves in the perspective of people with disabilities. This allowed us to make our machine do what we needed it to, for anyone who was willing to work on this production line.”

While each team member had a specific position, they also helped in other areas. Team communicator, senior Laura Klions said, “Working on this project provided me with a bunch of new opportunities and experiences that I would not have had otherwise. I really enjoyed learning a bit about construction, specifically how to weld.”

While each team member had a specific position, they also helped in other areas. Team communicator, senior Laura Klions said, “Working on this project provided me with a bunch of new opportunities and experiences that I would not have had otherwise. I really enjoyed learning a bit about construction, specifically how to weld.”

The team’s metal worker was senior Chris Dugan. He walked away from the final result stating, “Sometimes the biggest reward is not the one you expect. When I joined this team I knew it would be good experience for my future career in engineering. I did not think I would learn so much about people with disabilities, and I did not expect how good it made me feel to help out the workers at Weaver Industries.”

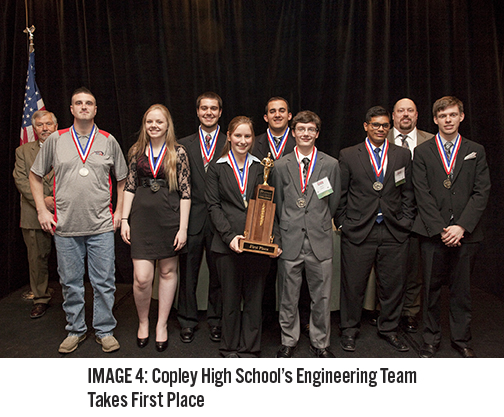

With the working model complete, Copley High’s engineering team submitted it as their entry in the SourceAmerica High School Design Challenge where they were awarded first place on the national level in Washington, D.C.

“The technology the students create for the SourceAmerica Design Challenge is game changing for the people who benefit from it,” said Steven Soroka, president and CEO of SourceAmerica. “Working side-by-side with an individual with a disability, these students implement ideas that change lives. Through their ingenuity, we are getting closer to the day when every person with a disability who wants a job has a job, and has the tools to be successful at it.”

“I don’t know of any other competition out there like this that has this kind of impact on the community,” said Charissa Garcia, Design Challenge Coordinator. “Graduates of this program received a patent for their technology. Participants also helped nonprofits secure contracts, which provide more employment opportunities for people with disabilities.”

When asked what it was like working on this project as a team, senior Josh Myers replied, “It was a great experience being on a team that enabled us to work and to function like real world engineers. We all did our best to help each other out, and support one another. This really contributed to our success. If we didn’t work so well together it would not have been nearly as easy to put in the long hours of work necessary to complete this project.”

Echoing that sentiment, the team’s leader, senior Rachel Hopkins stated, “It was a very real world experience; everyone on the team had a specific job to do based on what they could do, which enabled us to create something better than any one of us could have done alone.”

Upon congratulating his team on their national victory, Kirby Harper has begun looking forward to forming next year’s student engineering team. He is confident they will develop another tool that provides a better way of life for people with disabilities. We can count on seeing that tool in next year’s SourceAmerica High School Design Challenge as well.

Upon congratulating his team on their national victory, Kirby Harper has begun looking forward to forming next year’s student engineering team. He is confident they will develop another tool that provides a better way of life for people with disabilities. We can count on seeing that tool in next year’s SourceAmerica High School Design Challenge as well.

By TJ Johns, AutomationDirect

Originally Posted: May 21, 2015