This is part one of a two-part series on variable frequency drives. VFDs can reduce energy consumption, improve real-time control, and lengthen motor life; selecting the right one for your application requires asking the correct questions. Here are some expert tips to consider.

Determine if a VFD is right for your application.

The primary function of a variable frequency drive is to vary the speed of a three-phase ac induction motor. VFDs also provide non-emergency start and stop control, acceleration and deceleration, and overload protection. In addition, VFDs can reduce the amount of motor startup inrush current by accelerating the motor gradually. For these reasons, VFDs are suitable for conveyors, fans, and pumps that benefit from reduced and controlled motor

operating speed.

A VFD converts incoming ac power to dc, which is inverted back into three-phase output power. Based on speed setpoints, the VFD directly varies the voltage and frequency of the inverted output power to control motor speed. There is one caveat: Converting ac power to a dc bus — and then back to a simulated ac sine wave — can use up to 4% of the power that would be directly supplied to a motor if a VFD were not used. For this reason, VFDs may not be cost-effective for motors run at full speed in normal operation. That said, if a motor must output variable speed part of the time, and full speed only sometimes, a bypass contactor used with a VFD can maximize efficiency.

Consider your reasons for choosing a VFD.

Typical reasons for considering VFDs include energy savings, controlled starting current, adjustable operating speed and torque, controlled stopping, and reverse operation. VFDs cut energy consumption, especially with centrifugal fan and pump loads.

Halving fan speed with a VFD lowers the required horsepower by a factor of eight, as fan power is proportional to the cube of fan speed. Depending on motor size, the energy savings could pay for the cost of the VFD in less than two years.

Halving fan speed with a VFD lowers the required horsepower by a factor of eight, as fan power is proportional to the cube of fan speed. Depending on motor size, the energy savings could pay for the cost of the VFD in less than two years.

Using VFDs to operate fans and pumps can significantly reduce energy consumption, because they can tailor fan speed to the application. Fan horsepower is proportional to the cube of fan speed, so depending on motor size, energy savings can compensate for the initial VFD purchase price in less than two years.

Starting an ac motor across the line requires starting current that can be more than eight times the full load amps (FLA) of the motor. Depending on motor size, this could place a significant drain on the power distribution system, and the resulting voltage dip could affect sensitive equipment. Using a VFD can eliminate the voltage sag associated with motor starting, and cut motor starting current to reduce utility demand charges.

Controlling starting current can also extend motor life because across-the-line inrush current shortens life expectancy of ac motors. Shortened life cycles are particularly prominent in applications that require frequent starting and stopping. VFDs substantially reduce starting current, which extends motor life, and minimizes the necessity of motor rewinds.

The ability to vary operating speed allows optimization of controlled processes. Many VFDs allow remote speed adjustment using a potentiometer, keypad, programmable logic controller (PLC), or a process loop controller. VFDs can also limit applied torque to protect machinery and the final product from damage.

Controlled stopping minimizes product breakage or loss, as well as equipment wear and tear. Because the output phases can be switched electronically, VFDs also eliminate the need for a reversing starter.

In addition to varying speeds, conveyor applications typically require frequent starting and stopping. The picture to the right shows, VFDs substantially reduce starting current to extend motor life.

Select the proper size for the load.

When specifying VFD size and power ratings, consider the operating profile of the load it will drive. Will the loading be constant or variable? Will there be frequent starts and stops, or will operation be continuous?

Consider both torque and peak current. Obtain the highest peak current under the worst operating conditions. Check the motor Full Loads Amps (FLA), which is located on the motor’s nameplate. Note that if a motor has been rewound, its FLA may be higher than what’s indicated on the nameplate.

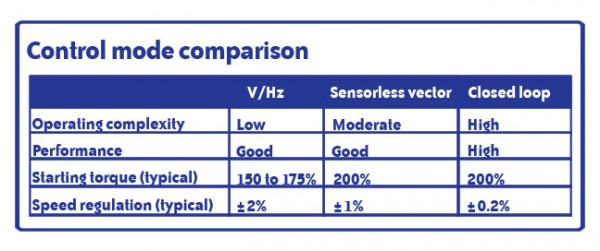

Web printing presses, paper mills, and material converting applications require the precise speed regulation of closed-loop control. For such cases, VFDs can be run in a closed-loop control mode. Elsewhere,volts-per-Hertz (V/Hz) and sensorless (or open-loop vector) modes are used.

Web printing presses, paper mills, and material converting applications require the precise speed regulation of closed-loop control. For such cases, VFDs can be run in a closed-loop control mode. Elsewhere,volts-per-Hertz (V/Hz) and sensorless (or open-loop vector) modes are used.

Don’t size the VFD according to horsepower ratings. Instead, size the VFD to the motor at its maximum current requirements at peak torque demand. The VFD must satisfy the maximum demands placed on the motor.

Consider the possibility that VFD oversizing may be necessary. Some applications experience temporary overload conditions because of impact loading or starting requirements. Motor performance is based on the amount of current the VFD can produce. For example, a fully-loaded conveyor may require extra breakaway torque, and consequently increased power from the VFD. Many VFDs are designed to operate at 150% overload for 60 seconds. An application that requires an overload greater than 150%, or for longer than 60 seconds, requires an oversized VFD.

Altitude also influences VFD sizing, because VFDs are air-cooled. Air thins at high altitudes, which decreases its cooling properties. Most VFDs are designed to operate at 100% capacity up to an altitude of 1,000 meters; beyond that, the drive must be derated or oversized.

Be aware of braking requirements.

With moderate inertia loads, overvoltage during deceleration typically won’t occur. For applications with high-inertia loads, the VFD automatically extends deceleration time. However, if a heavy load must be quickly decelerated, a dynamic braking resistor should be

used.

When motors decelerate, they act as generators, and dynamic braking allows the VFD to produce additional braking or stopping torque. VFDs can typically produce between 15 and 20% braking torque without external components. When necessary, adding an external braking resistor increases the VFD’s braking control torque — to quicken the deceleration of large inertia loads and frequent start-stop cycles.

Determine I/O requirements.

Most VFDs can integrate into control systems and processes. Motor speed can be manually set by adjusting a potentiometer or via the keypad incorporated onto some VFDs. In addition, virtually every VFD has some I/O, and higher-end VFDs have multiple I/Os and full-feature communications ports; these can be connected to controls to automate motor-speed commands.

Most VFDs include several discrete inputs and outputs, and at least one analog input and one analog output. Discrete inputs interface the VFD with control devices such as pushbuttons, selector switches, and PLC discrete output modules. These signals are typically used for functions such as start/stop, forward/reverse, external fault, preset speed selection, fault reset, and PID enable/disable.

Discrete outputs can be transistor, relay, or frequency pulse. Typically, transistor outputs drive interfaces to PLCs, motion controllers, pilot lights, and auxiliary relays. Relay outputs

usually drive ac devices and other equipment with its own ground point, as the relay contacts isolate the external equipment ground. The frequency output is typically used to send a speed reference signal to a PLC’s analog input, or to another VFD running in follower mode.

Typically, general-purpose outputs of most VFDs are transistors. Sometimes one or more relay outputs are included for isolation of highercurrent devices. Frequency pulse outputs are usually reserved for higherend VFDs.

Analog inputs are used to interface the VFD with an external 0 to 10 VDC or 4 to 20 mA signals. These signals can represent a speed setpoint and/or closed loop control feedback. An analog output can be used as a feedforward to provide setpoints for other VFDs so other equipment will follow the master VFD’s speed; otherwise, it can transmit speed, torque, or current signals back to a PLC or controller.

In Part Two, we will discuss selecting the proper control mode, understanding your control profile requirements, and more. Read Part Two here: http://library.automationdirect.com/top-10-tips-specifying-vfds-part-two-of-a-two-part-series-issue-21-2011/

This article originally appeared in the February 2011 issue of MSD magazine.

By Joe Kimbrell,

AutomationDirect

Drives, Motors, and Motion Control

Product Manager

Originally Posted: June 1, 2011